Two weeks ago Japan launched a spacecraft called 'Hayabusa 2', with

a twofold mission: Bring back samples of a half mile wide asteroid called 1999 JU3, and deploy a small fleet of sub-craft to explore it in detail:

Above Hayabusa 2 lifts off on it's mission to 1999 JU3. Again, what's with the uninspiring place names astronomers?

OK, rocket launches are cool (so are bowties I'm told), but 1999 JU3 sounds like a dull part of the cosmos. So..... why has

NASA's office of planetary protection recommended that any samples the mission brings back should be classed as category 5; to be handled with "strict containment"?

Is that asteroid a just tiny chunk of lifeless rock adrift in the void, or something more?

Is there something terrible and sinister going on?

Above: I have been waiting for an excuse to use this clip in something since, like, forever.

Y'see, one of the planetary protection guy's jobs at NASA is to assess what the odds are that material coming back to Earth could have ever hosted life. If their verdict is yes then it potentially (but still very, very unlikely) could contain something harmful. They do this by working their way through a simple check list of questions, because bureaucracy I guess.

Lets look at the page of the p

lanetary protection report that sums up the questions:

If you're interested in the fine details have a look at the link above. But, holy cow, that looks like there's a fair chance this miniscule asteroid was once habitable. Good god, could Haybusa accidentaly bring back alien bugs?

Almost certainly NO. In fact, the 'category 5' rating is a technicality - but it's one that reveals whole point of the Hayabusa 2 mission.

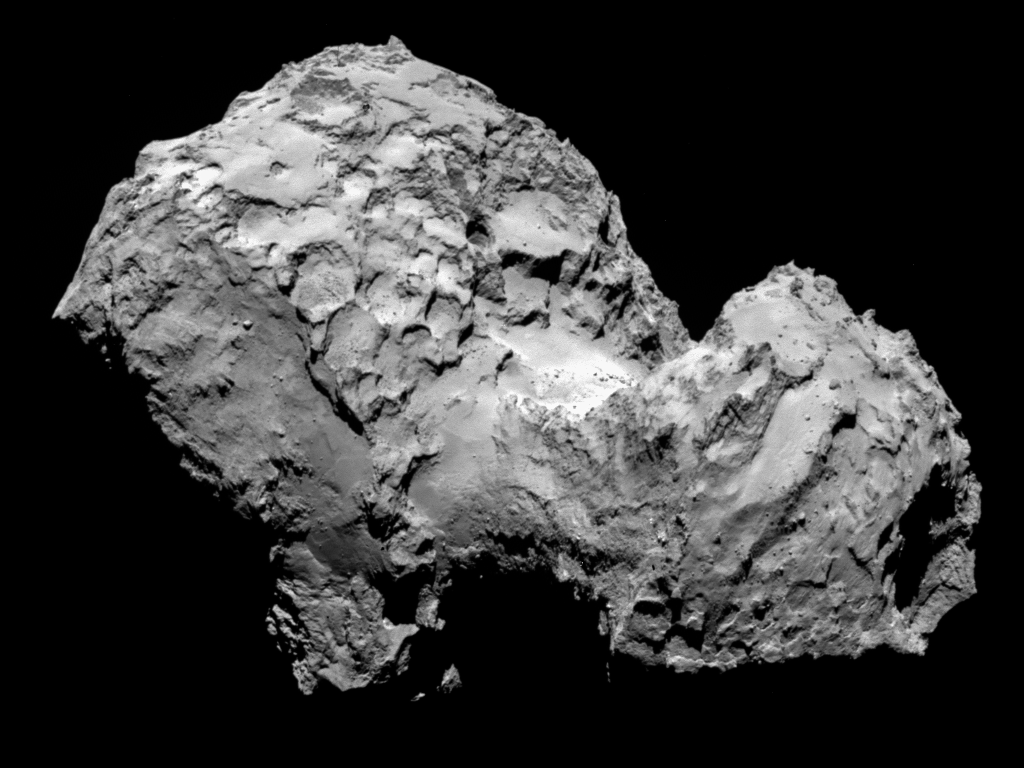

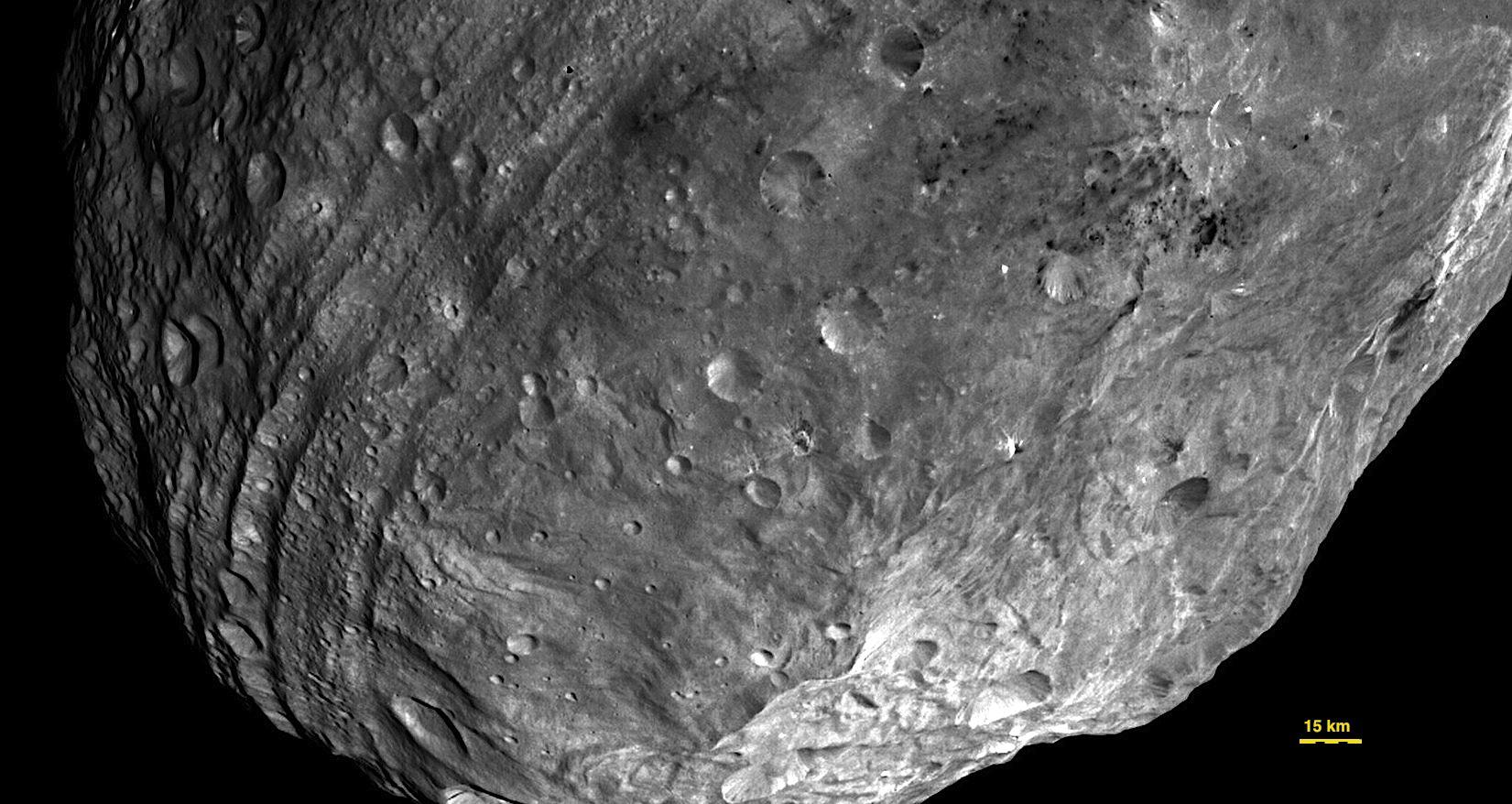

It's been known for a long time that space rocks like 1999 JU3 could be fragments of

protoplanets that had

carbon chemistry,

liquid water running beneath its surface, and energy sources like sunlight and radioactivity. These things are what we look for in a habitable world, but this tiny asteroid last saw liquid water and warmth

four billion years ago. That's before life itself had begun. That water was likely trickling through the tiniest of pore spaces in rocks, as ice melted - hardly Barbados! But yes, if we follow the reasoning strictly this was

technically a habitable place.

And that's the whole point of visiting this dull little place: It had all the conditions that life likes, all the conditions that organic chemistry needs to form life-like chemicals and processes. Earth had these, but life itself would have consumed them. 1999 JU3 could have preserved traces of the primordial processes leading up to the creation of life, but here life never came along to muddy the chemical waters, and wipe out any traces.

That's why Japan is sending a craft to visit it. And that's why NASA's 'strict containment ' verdict isn't a prediction of alien space germ doomsday, it's a promise of great discoveries in the making.

Elsewhere on the internet news:

Minute fragments of diamond revel the complex, and watery, history of a meteorite and it's parent world.

Another meteorite carries evidence of the proto-planetary disk that gave birth to our solar system.

A proposal for a robot radio observatory on the Moon's far side, that could probe the earliest times of the Universe and the most distant parts of it.

Here's an idea to protect your heirlooms: Send the m to the Moon!

A UK organisation aims to launch a publicly funded mission to the Moon's south pole.

And lastly, New Scientist magazine has had enough of all the delays stopping space agencies visiting Jupiter's ocean moon Europa, and is aiming to land its own probe there!